War and remembrance

One hundred years ago this month, World War I came to an end. At least 1,800 Rotarians from North America and Great Britain served in the military during that war; hundreds more enlisted in the Red Cross, the YMCA, and various government departments. More than 50 gave their lives. On the anniversary of Armistice Day, we look back at how the war unfolded in the pages of The Rotarian.

1914–15

“Whereas war is universally recognized as a bloody weapon handed down from a dark past … [Rotary should] lend its influence to the maintenance of peace among the nations of the world without recourse to war.”

An illustration shows the Lusitania sinking off the coast of Ireland.

So resolved the nearly 1,300 Rotarians who gathered at Houston’s Municipal Auditorium in June 1914 for the fifth annual convention of the International Association of Rotary Clubs. The Rotarian published the entire 183-word resolution in its August issue. But by then, the dominoes had fallen. On 28 June, two days after the convention adjourned, a 19-year-old Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, Sophie, in Sarajevo. On 4 August, Germany invaded Belgium, and within weeks, Germany and its ally, Austria-Hungary, were at war with France, Great Britain, Russia, and Serbia. The lamps had gone out all over Europe.

Buffered by the Atlantic Ocean, U.S. Rotarians were at first only indirectly affected by the war. At the Houston convention, a Texas Rotarian named R.C. Duff captured the mood that would prevail throughout the American branch of the organization for at least another year. Duff delivered a paean to business — “honorable, energetic, wealth producing commerce, trade and industry” — as “the panacea to war.” In the October issue of The Rotarian, L.D. Hicks, a founding member of the Rotary Club of Atlanta, introduced a catchphrase: “Don’t talk war, talk business.”

In their hands-off stance, these Rotarians mirrored President Woodrow Wilson, who on 4 August had issued a proclamation of neutrality. “The United States must be neutral in fact, as well as in name,” he said two weeks later in a message to Congress. “We must be impartial in thought, as well as action.” U.S. Rotarians anticipated that the distant perch from which they observed the “slaughter of humanity” fit them for a special role. “Let us, as Americans, do what we can,” pleaded the Rotary Club of Minneapolis. “We must not take sides. We cannot interfere. But we can give to the voice of peace a volume that will penetrate the confusion of the most impassioned battle.”

Calls for Rotary to serve as peace advocates came from outside the organization as well. In a September speech to the Rotary Club of Houston, writer and publisher Elbert Hubbard deemed Rotary “the greatest business organization in the world” and urged it “to lend its powerful influence toward universal peace.”

In 1914, Hubbard enjoyed a fame surpassed by few other Americans. With his shaggy mane, broad Stetson, baggy overcoat, and flowing cravat, he cut a distinctive figure, and he backed up his celebrity with prodigious output that included lively monthly magazines — most notably, The Philistine, his “periodical of protest” — and wares produced at Roycroft, his arts and crafts community near Buffalo, New York.

On 7 May 1915, Hubbard and his wife, Alice, were aboard the Lusitania near the coast of Ireland when a German torpedo ripped through the ship’s bow. The Lusitania sank within minutes. The Hubbards were among the nearly 1,200 dead — as was William Mitchelhill, a 44-year-old seed wholesaler from St. Joseph, Missouri, whose Rotary club memorialized him as “a man of unequaled personality, particularly known for his friendship, charity and love for his fellow men.”

The sinking of the Lusitania brought the war home to Americans. Frank Higgins captured that changing mood when he spoke at the sixth Rotary Convention, held in San Francisco in July 1915. One of Rotary’s vice presidents, Higgins was also president of the Rotary Club of Victoria, British Columbia. As part of the British Empire, Canada had already been at war for nearly a year. The world, Higgins lamented, beneath its “veneer of culture, education and refinement,” remained as brutally base as ever. “This is borne out,” he said, “by the fact that the bloodiest war that the world has ever seen is going on today, where men are killing one another as the savages did in the dark ages.”

Higgins feared that “the doctrine of peace and goodwill to all men will remain an aerial nothing” — unless “some uplifting force is injected into the world.” Rotary, he believed, was “that spirit, that force … ever swelling in volume and increasing in strength.”

1916

Despite evolving perspectives, those not fighting on the front lines struggled to comprehend the conflict. A Rotarian from England, visiting a strategic bridge in Edinburgh, marveled that “the sight of sentries, barbed wire and loopholed sand bag protections brought the war much nearer than we realise it in Manchester, as also did the inspiring sight of the (Royal Navy’s) fleet” anchored in the Firth of Forth.

American pacifists (including Jane Addams, third from left) travel to an international conference.

On 1 July, in northwest France along the Somme River, British troops stormed the entrenched German army. By day’s end, they had suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 soldiers dead from their wounds. Winston Churchill called it “the greatest loss and slaughter sustained in a single day in the whole history of the British Army.”

Fighting continued along the Somme for another 140 days, engaging about 3.5 million men from 25 countries. By mid-November, when winter weather brought fighting to a halt, British forces, which included troops from Australia, Canada, India, Ireland, and Scotland, had suffered about 420,000 casualties; the German army sustained at least 430,000, and France, 204,000. The maddeningly snail-paced nature of the fighting meant the daily advance or retreat of armies was often calculated in inches and feet and yards.

In November 1916, readers of The Rotarian got an unexpected glimpse into the trenches along the Somme. Weeks earlier, George Brigden, a future president of the Rotary Club of Toronto, had received a letter from a Canadian lieutenant named F.G. Diver. Dated 11 September, it began: “You will no doubt be quite surprised to receive a letter from me but I felt that I wanted in some way to show my appreciation to you for putting me into the Rotary Club and to let you know that even in the front line trenches away over here in France that I have felt its influence.”

Diver went on to explain that, while in England with a Canadian division formed in Ontario, he had been “one of the lucky” officers ordered to proceed immediately to France, where he joined the 87th Battalion, a Montreal unit known as the Canadian Grenadier Guards. Not knowing any of the officers, he had found it “pretty hard ... to break in to their little circle.” During a lull in the fighting, he stepped into another officer’s dugout “to have a smoke and incidentally see if he had anything on the hip, as it gets mighty chilly around here between four and five in the morning.”

That other officer turned out to be Major H. LeRoy Shaw, a founding member and former president of the Rotary Club of Montreal. What’s more, as Diver learned, two other officers in the 87th were also Rotarians: Majors Irving P. Rexford and John N. Lewis. “From that night on,” explained Diver, “it has made quite some difference for me, for, altho I am not yet one of their happy little family, I am a whole lot nearer than I would have been if it had not been for good old Rotary.”

Before signing off “Yours Rotarily,” Diver described the “great life” in the trenches. “Live like so many rats in the earth and, like rats, never change your clothes. ... But with all the inconveniences there is something that makes you glad you came.”

A little after noon on 21 October, during fighting east of the Ancre River, a tributary of the Somme, the Canadian Grenadier Guards seized a German position called Regina Trench. Leading his platoon, Diver died in the attack.

Four weeks later and less than a mile north from where Diver had fallen, Lewis met the same fate. Born in Tennessee in 1874 and a graduate of the universities of Chicago and Heidelberg, Lewis had worked for a Chicago newspaper before moving on to become editor of the Montreal Star. Second in command, behind Shaw, of the 87th’s No. 1 Company, he had won the Distinguished Service Order for his heroism in the attack on Regina Trench. A little before dawn on 18 November, as a driving rain turned to snow, the Grenadier Guards climbed from flooded trenches and slogged under enemy fire across a muddy no man’s land to yet another German bulwark, this one called Desire Trench. By 8 a.m., the Guards had captured the position, and Lewis was dying, or perhaps already dead.

Rotarian and star vaudevillian Harry Lauder and his son, John.

His obituary in the Star noted that Lewis, a founder of the local Boys’ Club, had, in both Chicago and Montreal, contributed generously “to charitable organizations having the care and upliftment of children as their special concern.” In Lewis’ memory, the Montreal Rotary club raised $10,000 to erect a building at the Shawbridge Boys’ Farm in Quebec with a brass plaque inscribed, “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.” (Home to 30 boys, the two-story brick Lewis Memorial Cottage stood until the 1960s.) As for Shaw and Rexford, they survived the war and returned to Montreal, Shaw to pursue his prewar insurance career (and his passion for curling) and Rexford to assume the presidency of the club, where, in 1929, he led a successful campaign to raise more than $250,000 for the Boys’ Home Fund.

The year closed with one more Rotary-related death as the son of Harry Lauder fell in France. A pawky Scotsman — the modifier, often affixed to his name, connotes someone who is humorously tricky or sly — the elder Lauder cultivated an instantly identifiable public persona, which in his case entailed wearing a kilt and tam-o’-shanter, smoking a short clay pipe, and wielding a gnarled cromach, or walking stick. A singer, songwriter, and comedian, he packed vaudeville theaters in Britain, Australia, Canada, and the United States and sold, by his own estimate, a million or more records. During the first two decades of the 20th century, he was the highest-paid performer in the world.

At the end of 1914, the Rotary Club of Glasgow “installed” Lauder as a member, though the entertainer claimed to have joined Rotary earlier that year while touring America. (Rotary lore has it that Lauder met Paul Harris while performing in Chicago and that the two men became fast friends.) Lauder was effusive in his praise for Rotary, and he regularly appeared at Rotary clubs, where he would lead members in song, including one he had written whose chorus began: “In the Rotary, in the Rotary / That’s the place to find sociability.”

Over the Christmas holidays in 1916, Lauder was performing at a London theater in a revue called Three Cheers, which regularly drew soldiers on leave from France — men, as Lauder explained, who were looking for “something light, with lots of pretty girls and jolly tunes and people to make [them] laugh.” On New Year’s morning, a banging at his hotel door awakened him. A porter handed him a telegram: Four days earlier, at about 8 in the morning, his 25-year-old son, John, a captain with the 8th Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, had been killed by a German sniper near the French town of Pozières. John Lauder had been about to return home on leave.

Lauder’s death hit U.S. Rotarians hard. The New York City club sent his father a tribute written by one of their members, author and editor F.D. Van Amburgh. The Rotarian published the prose poem in its February 1917 issue. “Can’t you see us, Harry?” its third stanza asked. “Can’t you understand that this is not alone your loss? This is an international sorrow that borrows from Rotarian hearts the warmest glow.”

In his memoir, A Minstrel in France, Harry Lauder recalled how the news of his son’s death nearly led him to end his career. However, he did return to Three Cheers, compelled to provide for others a brief respite from the misery of war. In June 1917, he visited British troops in France, where soldiers begged, “Make us laugh again, Harry!” (His wartime service, which included recruitment drives, hospital visits, and bond rallies, earned Lauder a knighthood in 1919.)

During that 1917 tour, Lauder visited his son’s grave on the Somme battlefield. (Today, the Ovillers Military Cemetery contains the graves of 3,440 Commonwealth war dead; more than 70 percent of the burials are unidentified.) Lauder collapsed on the mound beneath the white cross where his son lay. “As I look back upon it now,” he wrote, “I can think of but the one desire that ruled and moved me. I wanted to reach my arms down into that dark grave, and clasp my boy tightly to my breast, and kiss him. And I wanted to thank him for what he had done for his country, and his mother, and for me.”

1917

On 7 November 1916, after campaigning under the slogan “He kept us out of war,” Woodrow Wilson won a second term as president. On 2 April 1917, four weeks after his inauguration, he addressed a special session of Congress and asked for a declaration of war against Germany. Within days, the House and Senate gave Wilson what he wanted.

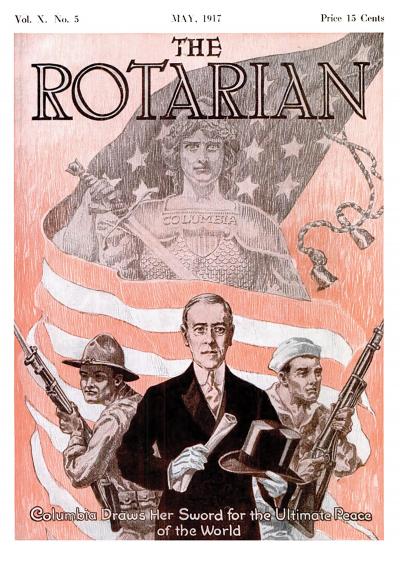

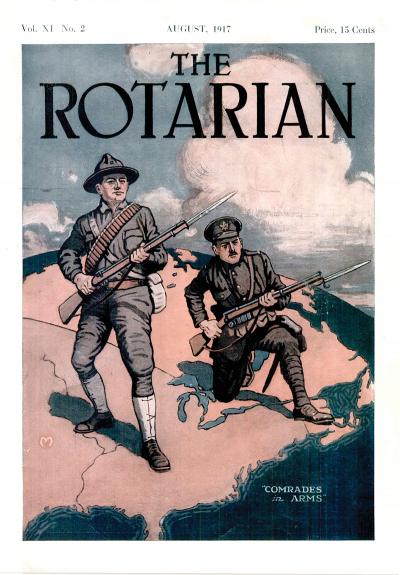

Covers of The Rotarian published in 1917.

An honorary member of several Rotary clubs, Wilson was later eulogized by The Rotarian as “an apostle of peace.” But after the Germans rejected his attempts to negotiate an end to the war, resuming unrestricted submarine warfare and hatching a plan to lure Mexico into the conflict by promising to help it recover its former territory in the American Southwest, Wilson had had enough.

The Rotarian supported the president. “In his call to the democrats of the world,” it editorialized in May, “President Wilson has placed before them, in a clear light, the Rotary principle of SERVICE ABOVE SELF — service for the whole world — above [the] self interest of any nation.” In the same issue, a full-page ad festooned with American flags and bearing the boldface headline “WAR” promised that the upcoming annual convention would “give additional support to the President of the United States, by the most wonderful demonstration of business and professional men ever assembled at a Convention. Don’t fail to come to Atlanta, where International Rotary History will write its greatest chapter.”

Too ill to attend the convention, Paul Harris sent a message to be read there, in which he extolled Wilson — “the ideal of American citizenship” — and turned an optimistic eye toward the potential benefit of war. “These are mighty days, days of incomparable opportunity — of opportunity undreamed,” he wrote. “Off with the useless old, on with the useful new. There will never be a better chance than now. Humanity must rise triumphant from this vale of sorrow, ennobled by its suffering.”

With all this came a decided change in the tenor of this magazine. Gone was the monthly News of the Clubs column, replaced by updates about “Clubs Busy at Patriotic Tasks” and “War Service Work by Rotary Clubs.” Rotarians pitched in to pay for ambulances and other martial necessities, and they contended to outdo one another with their contributions. Members of the Rotary Club of Utica, New York, purchased $330,000 in Liberty Bonds as part of its Win the War effort.

Of course, The Rotarian had carried reports of such civic projects, especially from parts of the British Empire, all along. During the summer of 1915, for instance, Ireland’s Rotary Club of Belfast generously contributed to a local ambulance fund. That autumn, Rotarians in Dublin “spent a considerable portion of [their] energies in entertaining wounded soldiers.” And as the year ended, Rotarians in Hamilton, Ontario, staged “many fetes and other public affairs ... to raise money for the needs of soldiers at the front.”

In September 1917, on War Department stationery, Raymond B. Fosdick, chairman of the commission on training camp activities, wrote a letter of appreciation to Chesley Perry, editor of The Rotarian and Rotary’s first general secretary (though that specific title didn’t exist yet). “I am so impressed with what your organization has done that I have brought it to the attention of both the Secretary of War and the President,” Fosdick wrote. President Wilson followed up with his own letter to Perry in which he acknowledged that “the service rendered by your organization in this time of national stress has been very great, and I feel that you are making a genuine contribution to the cause which we all have so much at heart.”

The names of distinguished Americans began to appear in the magazine alongside wartime messages. Major General Leonard Wood wrote about “The New American Army.” U.S. Food Commissioner and future President Herbert Hoover preached the “gospel of the clean plate,” outlining ways to save meat, milk, fats, sugar, and fuel. “The way to win,” he said, “is to stop wasting.” Walter Camp, the “father of American football” — from 1888 to 1892, his Yale teams went 67-2 — laid out his idea for a Senior Service Corps that would allow men over age 45 “to become efficient patriots.”

War-themed poems and declamations also became a regular feature of the magazine, literary lucubrations titled “For France!” or “The Age-Long Battle” or “The Kid Has Gone to the Colors.” They aimed to uplift, but there were hints of despair. In December, Philip R. Kellar, managing editor of The Rotarian, offered “The Message of This Christmas.” It began:

O warring, biting, hate-filled world!

O world all bleared and sodden with the blood

Of countless victims of the wrath of war ...

Where murder, rapine, lust, deceit and lies

Have been unleashed to prey, unchecked, on man!

The poem’s final stanza sounded a note of hope, but could not dispel the gloom. Like the rest of the country, Kellar was awakening to the carnage that was still to come.

1915–18

In July 1919, eight months after Armistice Day, The Rotarian printed its Gold Star Roll of Honor, listing club members “who gave their lives in the service of their countries and humanity.” It contains the names of 47 Rotarians: Twenty-six were from the United States, nine from Canada, eight from Scotland, and four from England — and there were at least six more Rotarians whose names should have appeared on the honor roll but did not. (There were no Rotary clubs in continental Europe or Australia until after the war.)

View Slideshow

View Slideshow

A U.S. gun crew advances on an entrenched German position.

Captain Richard Steacie was the first Rotarian to die in the war. A member of the 14th Royal Montreal Regiment, Steacie was shot through the neck on 22 April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres in western Belgium. The dead soldier’s collar tag identified his rank and regiment but not his name, and he was buried beneath a gravestone inscribed: “A Captain of the Great War ... Known Unto God.” (Steacie’s body was finally identified in 2013.)

All the honor roll tells us of J.N. Henderson is that he was from Edinburgh, but a monument inside that town’s St. Giles’ Cathedral notes that he was a major with the 4th Royal Scots who died 28 June 1915, at the battle of Gully Ravine on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey. Another Edinburgh soldier, Lieutenant W.E. Turnbull of the 5th Royal Scots, also died at Gallipoli. Private C. Taylor of the 7th Manchester Battalion remains an enigma; he didn’t make the 1919 honor roll, but the December 1915 issue of The Rotarian mentions his death.

Not every Rotarian soldier died on the battlefield. Robert M. McGuire, a photographer from Joplin, Missouri, died on 4 July 1918 “from [an] operation to prepare him physically for entering service.” George Blakeslee of Jersey City, New Jersey, died of unknown causes 2 October 1918 at Camp Johnston, Florida. Frank Keator of Kingston, New York, died of pneumonia at Camp Devens, Massachusetts, on 29 December 1917. Two other Rotarians also died of pneumonia, and in a harbinger of the global epidemic, Captain Eugene H. Kothe of the Quartermaster Corps died of influenza in Washington, D.C., on 14 October 1918.

A star halfback at Kalamazoo College, Colonel Joseph B. Westnedge fought in the Spanish-American War, served on the Mexican border after Pancho Villa raided Texas and New Mexico, and led the 126th Infantry in the renowned 32nd “Red Arrow” Division during key offensives in France during World War I. On 29 November 1918, in a hospital in Nantes, Westnedge died of complications from tonsillitis. His name is missing from the Roll of Honor.

For Rotarians, the heaviest toll in battle came in 1918 after U.S. troops landed in Europe. Most fatalities came in the seven-week Meuse-Argonne Campaign that breached the Hindenburg Line, Germany’s last line of defense. Lieutenant Harry B. Bentley of Elmira, New York, died on 29 September near the St.-Quentin Canal; Lieutenant Edward Rhodes of Tacoma, Washington, died nearly two weeks later near Grandpré. Today, Bentley and Rhodes have American Legion posts named for them in their home states.

On 22 October, Private Jacob Ferdinand Speer of Wilmington, Delaware, whose name also does not appear on the honor roll, died near the bombed-out Madeleine Farm north of Nantillois. And on 4 November, a week before the war ended, Corporal Howard E. Brown of Lincoln, Nebraska, died in the advance on Stenay, a village on the Meuse River. The last Rotarian known to have fallen in combat during the War to End All Wars, Brown had written a member of his Lincoln club a few weeks earlier to thank him for forwarding “next year’s membership card.”

But Brown was not the final fatality. That distinction belongs to Griffin Cochran of Lexington, Kentucky. Regular readers of The Rotarian may have remembered Cochran’s name from before the war, when he provided updates about Rotary happenings in his hometown. As a club correspondent, he was, as the editors explained, one of the many “service-men whose co-operation makes our magazine successful.” Because this note appeared in 1916, the reference to service-men likely had no military association but instead referred to club members who assisted “The Magazine of Service,” The Rotarian’s slogan at the time.

In the spring of 1918, Cochran was a captain at Camp Zachary Taylor near Louisville. Cochran’s unit, the 309th Ammunition Train, eventually found its way to France, where it remained after the war ended. On 21 February 1919, Cochran died at Tours. His cause of death remains a mystery.

The 11th Hour of the 11th Day of the 11th Month

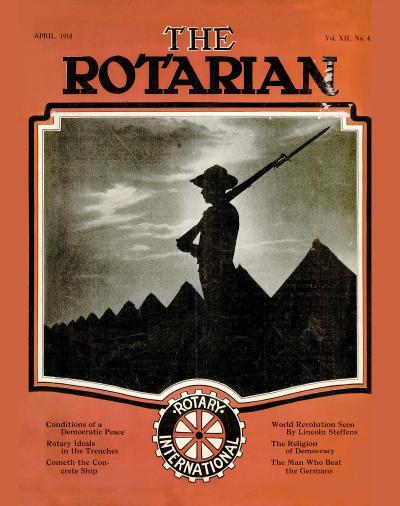

In April 1918, months before the war’s end, Rotary was already envisioning what a postwar world would look like. That month The Rotarian published an article by British writer Norman Angell called “Conditions of a Democratic Peace.” In it, Angell, who would win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1933, championed Wilson’s call for a League of Nations, a plan the president had been formulating since 1916.

A soldier stands vigilant on the cover of the April 1918 Rotarian, while inside, British writer Norman Angell looks forward to a peaceful postwar world.

A wounded doughboy enjoys chocolate and cake at a Red Cross hospital.

Like Wilson, Angell knew he was fighting an uphill battle. Nonetheless, he challenged those people who did not believe in the league because they thought it impractical. “The truth is that it is not practical because we do not believe in it,” he argued. “If we all believed in it and were determined to bring it about, that fact of itself would make it not only practical but inevitable.” Then Rotary’s prewar aspiration for “peace among the nations of the world” might finally be realized.

At 11 a.m. on 11 November, 47 miles northeast of Paris in the Forest of Compiègne, German delegates met with Allied commander Ferdinand Foch and signed the armistice that ended the war. Rotarians rejoiced. A more sanguine Philip Kellar characterized the armistice as “the greatest surrender in the history of humanity. It marked the ending of the battles of war and the beginning of the greater battles of peace.”

But in midterm elections held six days before the armistice was signed, Republicans won control of both chambers of Congress. Even a persuasive Democratic president would have a tough time beating those odds. Within months, “the idealism of wartime was fading into the problems of the postwar period,” recounted Yale historian John M. Blum. “Inflation, unemployment, and fears of Bolshevism” — this last was evident even in the pages of The Rotarian — “reduced public enthusiasm for a generous peace and for a genuine internationalism.” Congress never ratified the Treaty of Versailles, and though there would be a League of Nations, the United States would never become a member.

Even as Wilson’s dream collapsed, Rotarians imagined an international league of their own devising. Harwood Hull articulated that concept in an address to his Rotary club in San Juan, Puerto Rico. (Hull’s speech appeared in the December 1919 Rotarian under the title “A Rotary League of Nations.”) “The League of Nations and what it may accomplish to me seems no more of a dream, an idle vision, than Rotary itself,” Hull said. “The same things that make Rotary possible will make a league of nations possible — personal contact, fellowship, friendship, understanding, tolerance, confidence and, above all, serving others in our work. ...

“Some day there will be a Rotary league of nations. It may not be the league we hear about now, but the league that is to be can succeed only to the extent that the principles of Rotary are accepted and applied in the dealing between nations as they are coming to be more and more demanded and in our dealing with each other.”

• Read more stories from The Rotarian